Nina, how can you have such courage?

Photo, 2.10.2020 | CONTEMPORARY ART | PHOTO

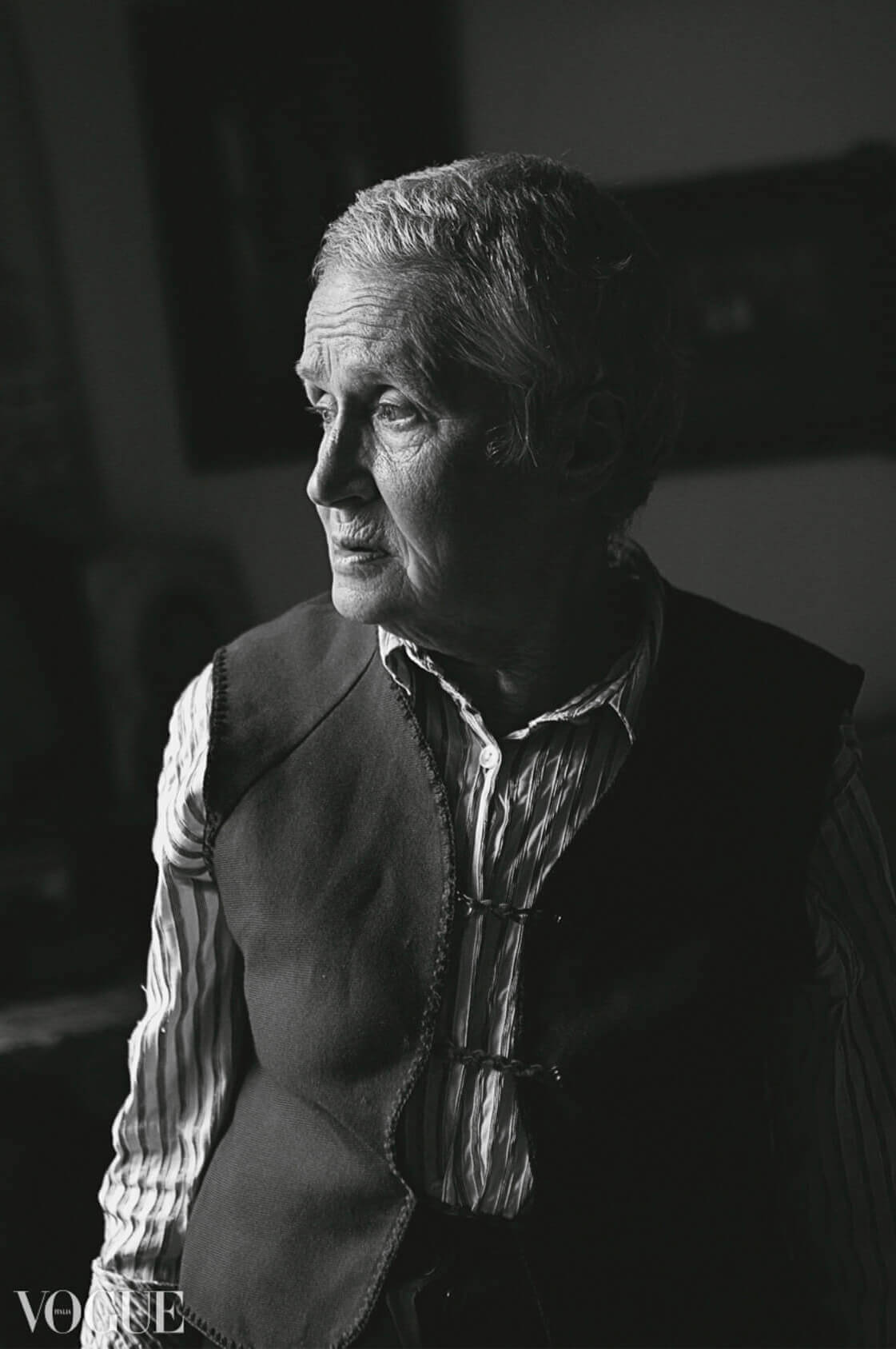

When we approach Nina Bagninskaya’s building, we immediately realize that the map hasn’t misled us: one of the balconies is cozily decorated in white and red. As she leads us up the stairwell, Nina Grigoryevna explains that it wasn’t her doing, but her granddaughter’s. At the entrance to the apartment, we’re greeted by a multicolored woven rug made by her own hands.

The Chrysalis Mag team visited one of the central figures of Belarusian protest art — and now we invite you to step into this atmosphere with us.

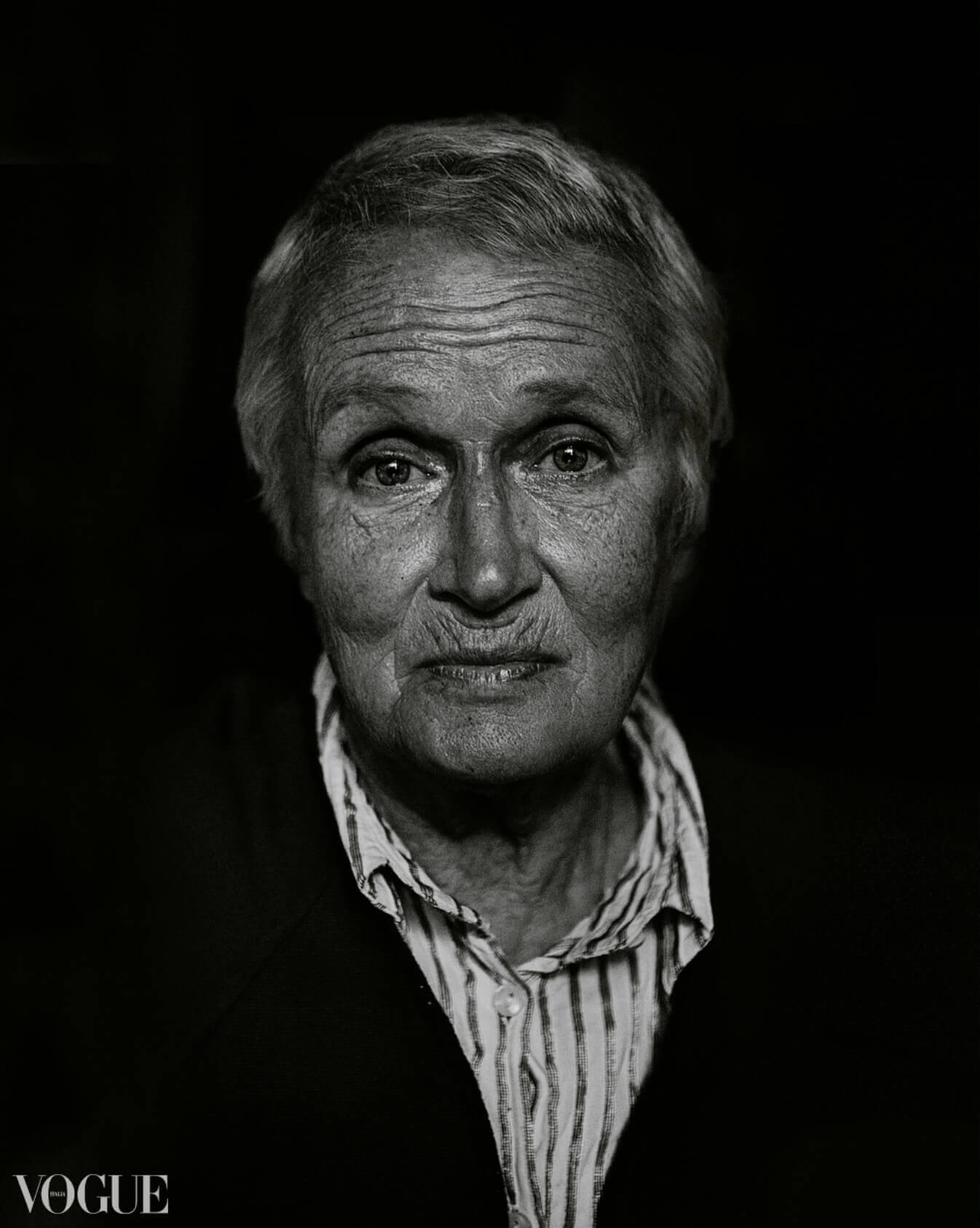

On the eve of our feature’s release, Vogue Italia published several portraits of Nina Bagninskaya on its website from the series “The Mother of the Belarusian Revolution.” To clarify: photographers submit their images themselves for moderation to the magazine’s web platform; however, the final selection for publication is made by an editor, who chooses what aligns with the publication’s interests and format.

SHARE:

Nina Bagninskaya is a legend and a political activist who has become a true symbol of Belarus.

She is 73 years old and has been taking part in protests against the current authorities since 1988. She has been detained dozens of times and arrested on multiple occasions. Nina has been repeatedly fined for various reasons: in 2016 alone, she owed the state more than $16,000 for participating in what were labeled “unauthorized events.” However, Bagninskaya has never paid these fines and has consistently refused financial assistance from human rights organizations.

“We didn’t talk for as long as I would have liked. To be honest, I don’t really remember what we talked about. Something about apples, garden beds, protests, Lukashenko, then apples and garden beds again. Toward the end, she said she had always wanted to have many children. I joked that she was the grandmother of the Belarusian revolution, and she said, ‘Nonsense,’ and smiled shyly.

Then I said:

‘Nina Grigoryevna, what would you say to Belarusians if you knew that everyone would hear you?’

She prepared herself for a long time. She thought for a long time.

‘I would pass on two things. First — that it’s impossible to be happy if a person is not free. One must fight for one’s freedom, fight for the land, for the language, for our people. The land and the people must be free. And happy.

And the second thing is that we must protect our nature. So that it is clean and good. We come from nature, and it is our duty to protect it.

And tell the internet that I love everyone.’

So, internet, I’m passing this on to you: she loves all of us. And she hugs all of us — small, thin, and so strong — the grandmother of all Belarusians, Nina Bagninskaya.”

Photo: Chrysalis Mag

Reproduction of this material or any part of it is permitted only with the written consent of the editorial team.

Нина Багинская — легенда и политическая активистка, ставшая настоящим символом Беларуси.

⠀

Нине 73 года, она выходит на акции протеста существующей власти с 1988 года. Ее задерживали десятки раз, несколько раз арестовывали. Нину постоянно за что-то штрафовали: в 2016-м она должна была государству больше 16 тысяч долларов за участие в «несанкционированных мероприятиях». Но Багинская ни разу не оплатила эти штрафы, при этом отказываясь принимать финансовую помощь от правозащитных организаций.

Фотографии: Иван Ревяко

Текст: Полина Юргенсон, Саша Дорашенко, Иван Ревяко

За то, что встреча с Ниной состоялась, благодарим Дашу Ржавцеву.

Перепечатка материала или фрагментов материала возможна только с письменного разрешения редакции.

Если вы заметили ошибку или хотите предложить дополнение к опубликованным материалам, просим сообщить нам.

We find ourselves in a room with high ceilings, typical of Stalin-era buildings. One wall is covered with numerous black-and-white photographs — the parents and grandparents of Nina Grigoryevna. Opposite them are hand-drawn posters depicting Bagninskaya.

“My granddaughter sometimes shows me paintings with my image online. I’ve seen that they’ve even started making brooches with me. Young people liked this ‘I’m out marching!’ of mine. At first I was shocked, because I’ve never been a reveler — I’ve always been more of a workaholic.”

“I’ve always had many hobbies. For example, sewing. I made this myself: I took old dresses, skirts, trousers — things that were worn out or out of fashion — and cut squares from the fabric, then create patterns: four fish and little frogs. At first I never know what it will turn into: I just start working, and only later choose and adjust things so that the colors fit together.”

“All my life I dreamed of having a garden. I was born in the city, so I was very jealous of children who lived in the countryside and could eat as many apples as they wanted. My mother would bring a kilogram of apples from the Komarovka market, and the three of us sisters would sit down and eat them all at once — and still want more. So when the Soviet Union collapsed and land began to be distributed, I immediately put my name down.”

“I really love woodcarving and working with interior design in general. At one point I even enrolled in woodcarving courses, because my love for wood is probably genetic. I’m not afraid of the forest — I love it, and I often go mushroom picking on my own. My hands are women’s hands, not strong enough for woodcarving, but I still try.”

“I had my children later in life and felt that I hadn’t fulfilled myself as a creative person. I signed up for dance classes. My husband laughed at first. So I told him, ‘I went to learn how to dance’ (laughs). Later I took up woodcarving, knitting, and weaving. The weaving courses, by the way, opened during the period of national revival, and that’s when I wanted to learn how to weave belts. Now, when I wear a skirt, I wrap one of my own belts around my waist.”

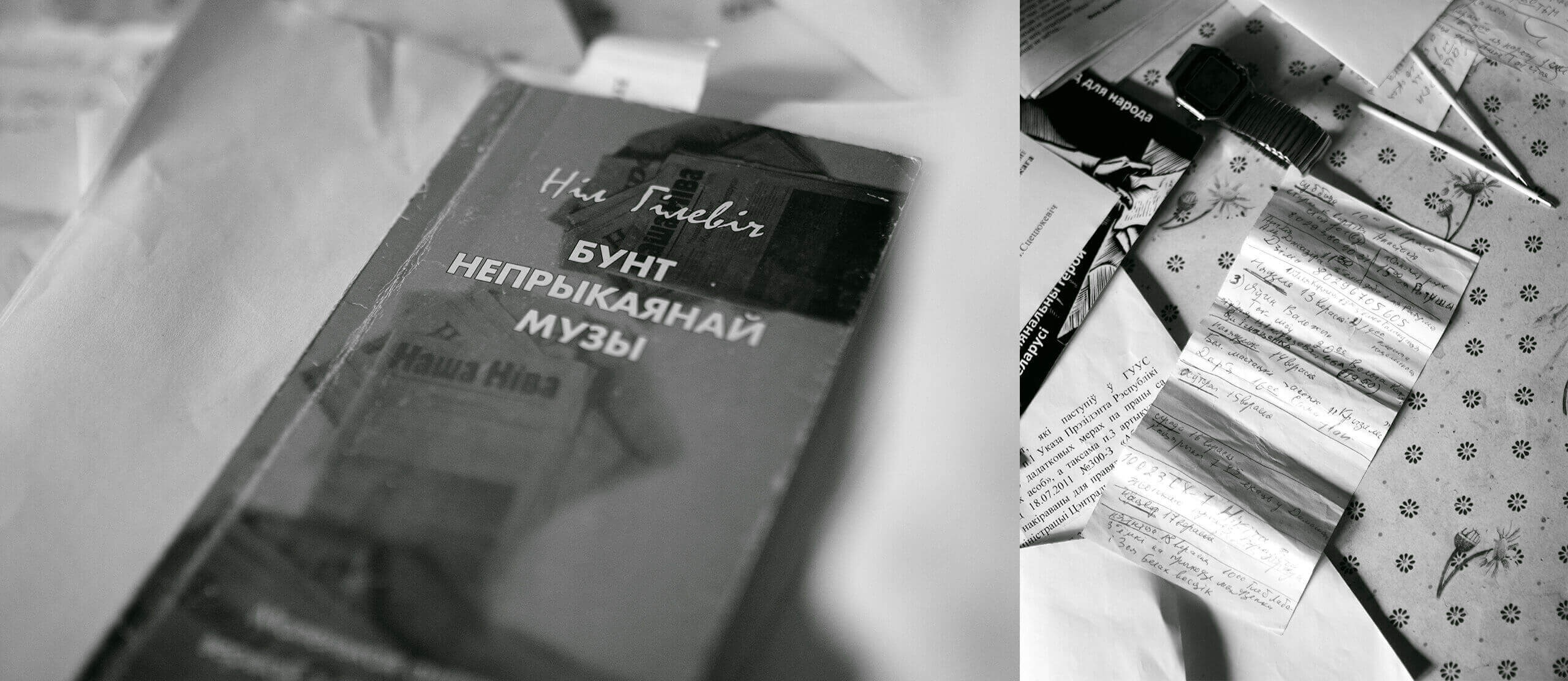

Letters written by Nina Grigoryevna to law enforcement authorities. In her own handwriting, Bagninskaya sets out her account of what happened during the first days of the protests, as well as a statement regarding the theft of the flags she sews herself and always brings with her to demonstrations.

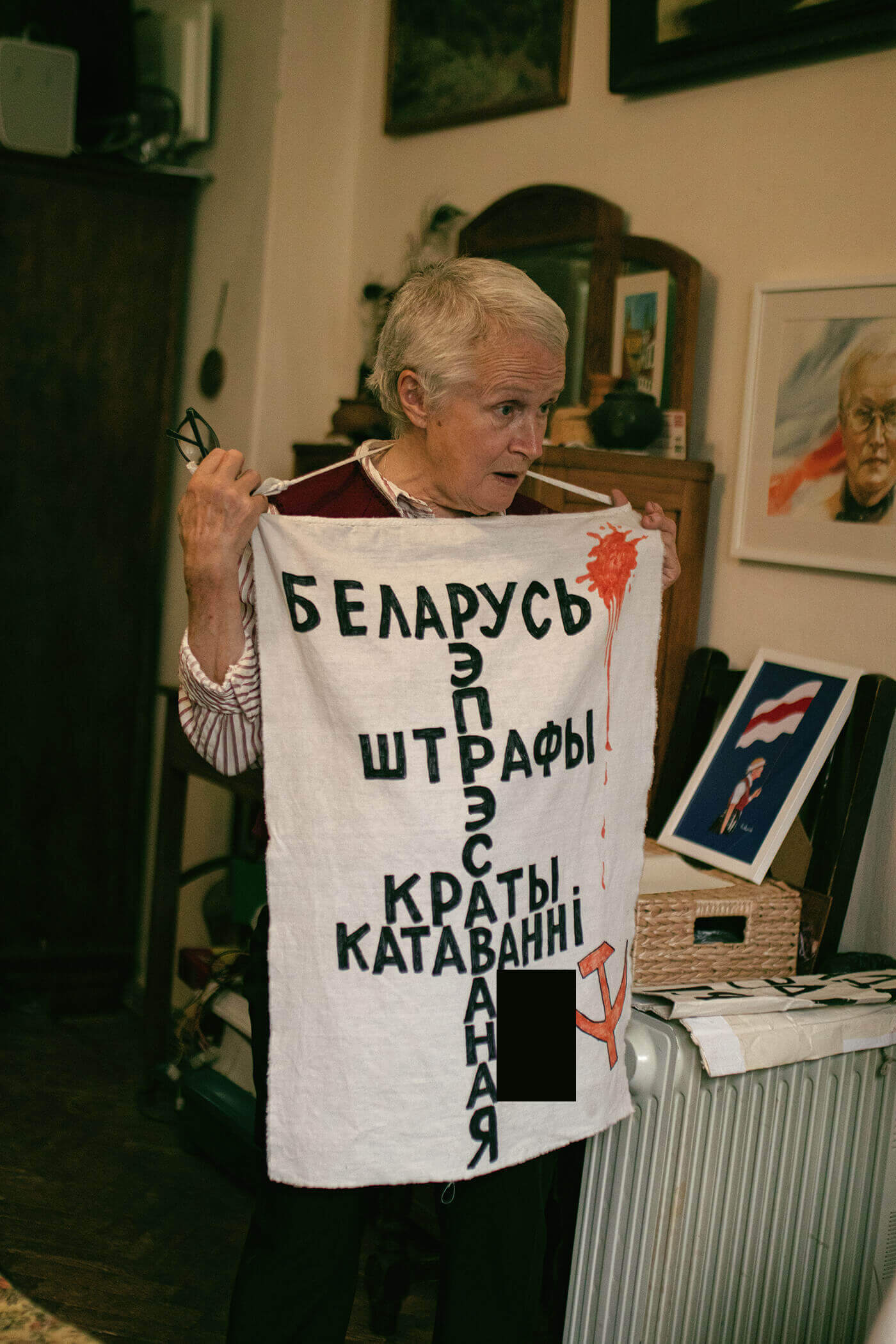

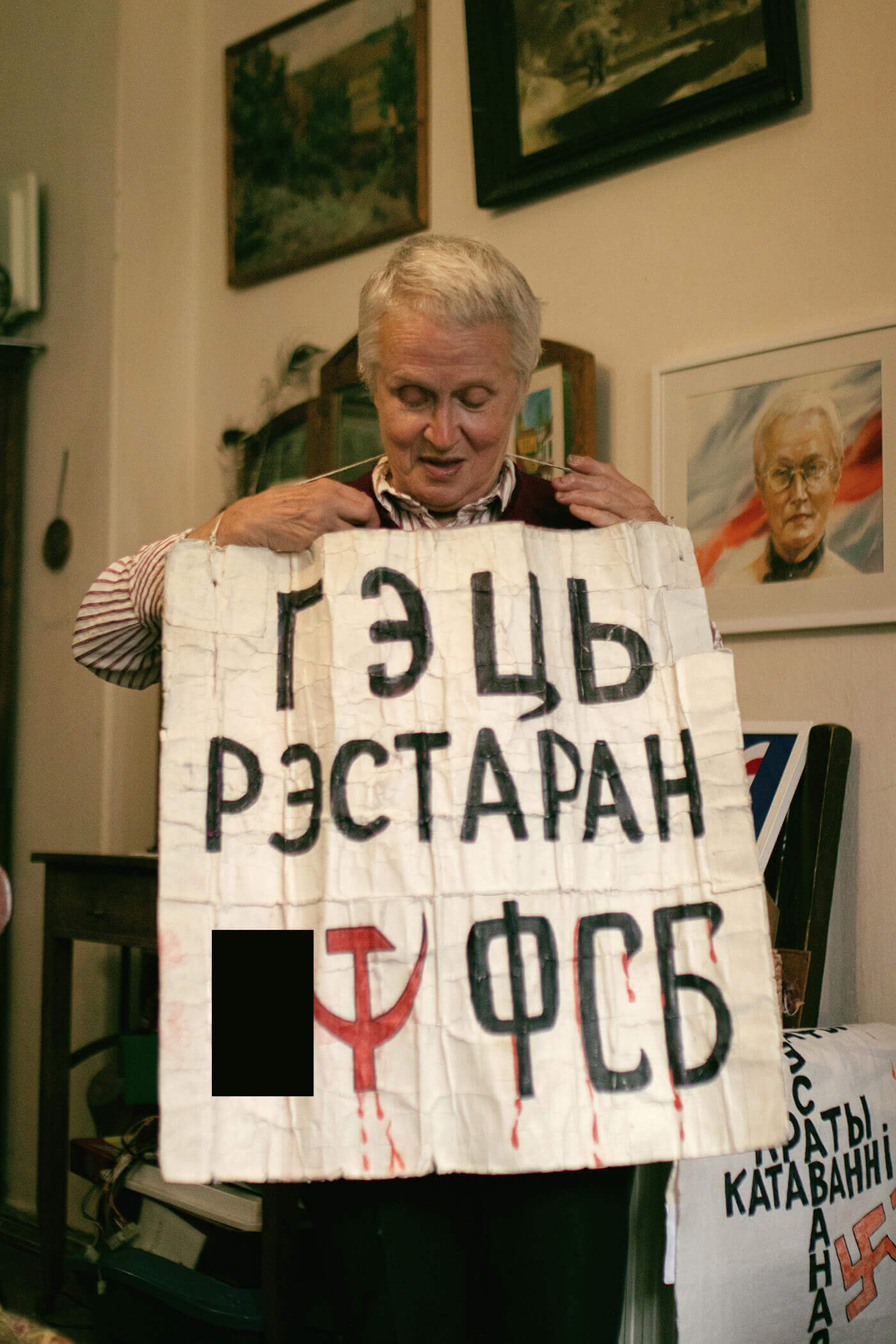

“This poster against the construction of a restaurant in Lebyazhiy, as you can see, has become very worn over two and a half years. But I don’t want to repair it, to show that even it has already torn, while the restaurant is still standing. Sometimes I come there and simply sit. Everything I do is not bravery, but simply dignity. People often ask me when they approach, ‘Nina, how can you be so brave?’ And at my age, you’re no longer afraid of such things.”

“People often want to take photos with me. I never refuse, because I think: one day your children will ask you, ‘What did you do back then, as parents?’ And you’ll tell them: ‘See this photo — this is us with Nina Bagninskaya, who had been fighting long before us, for 30 years. And that’s when we started going out too.’”

SHARE:

Related Materials