Curious about Soviet panel houses and what they mean today? Belarusian artist Liza Khikhlushka has just completed her most intimate series exploring this — and she shares why

Curious about Soviet panel houses and what they mean today? Belarusian artist Liza Khikhlushka has just completed her most intimate series exploring this — and she shares why

Interview | 06.07.2025

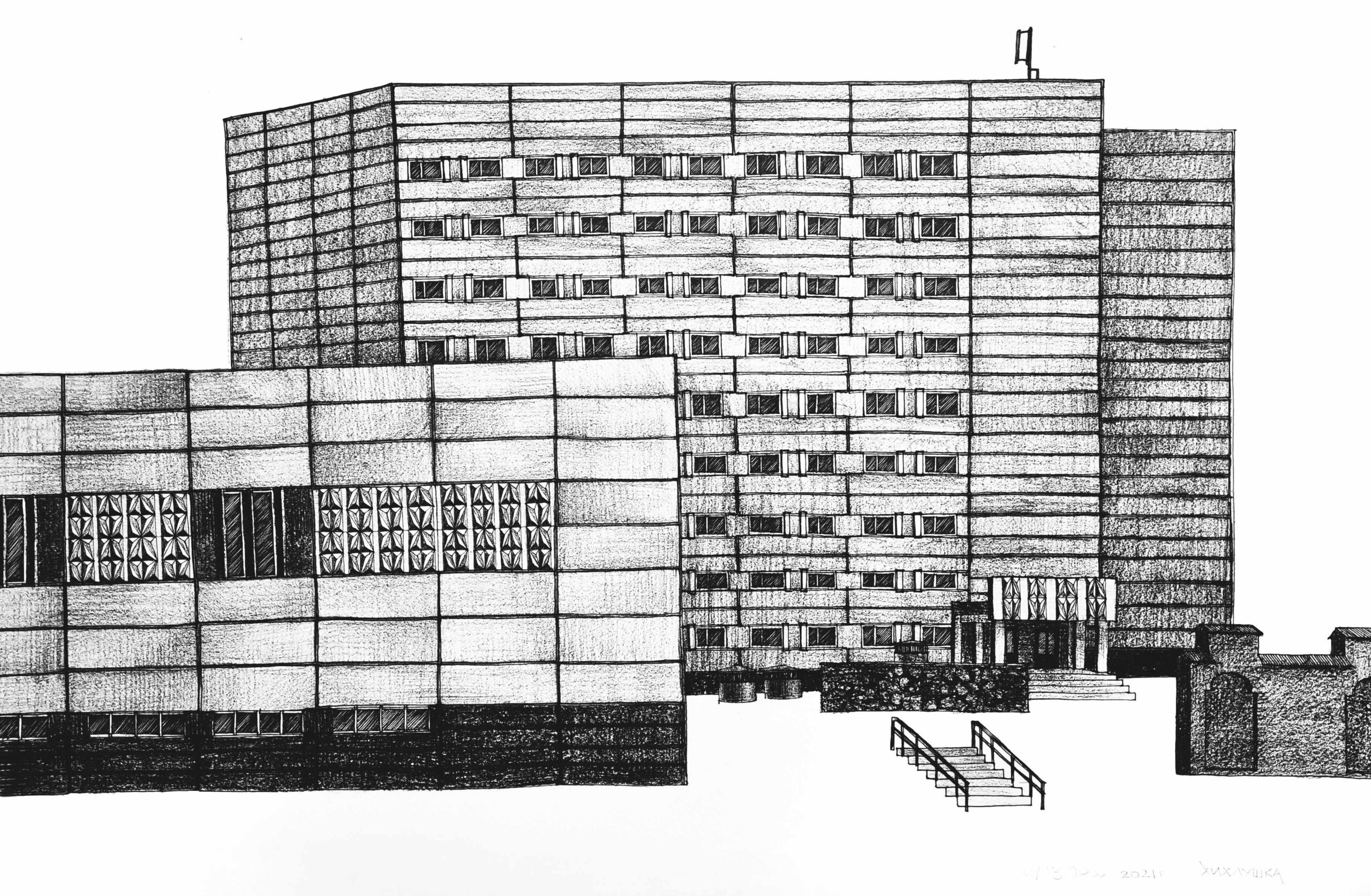

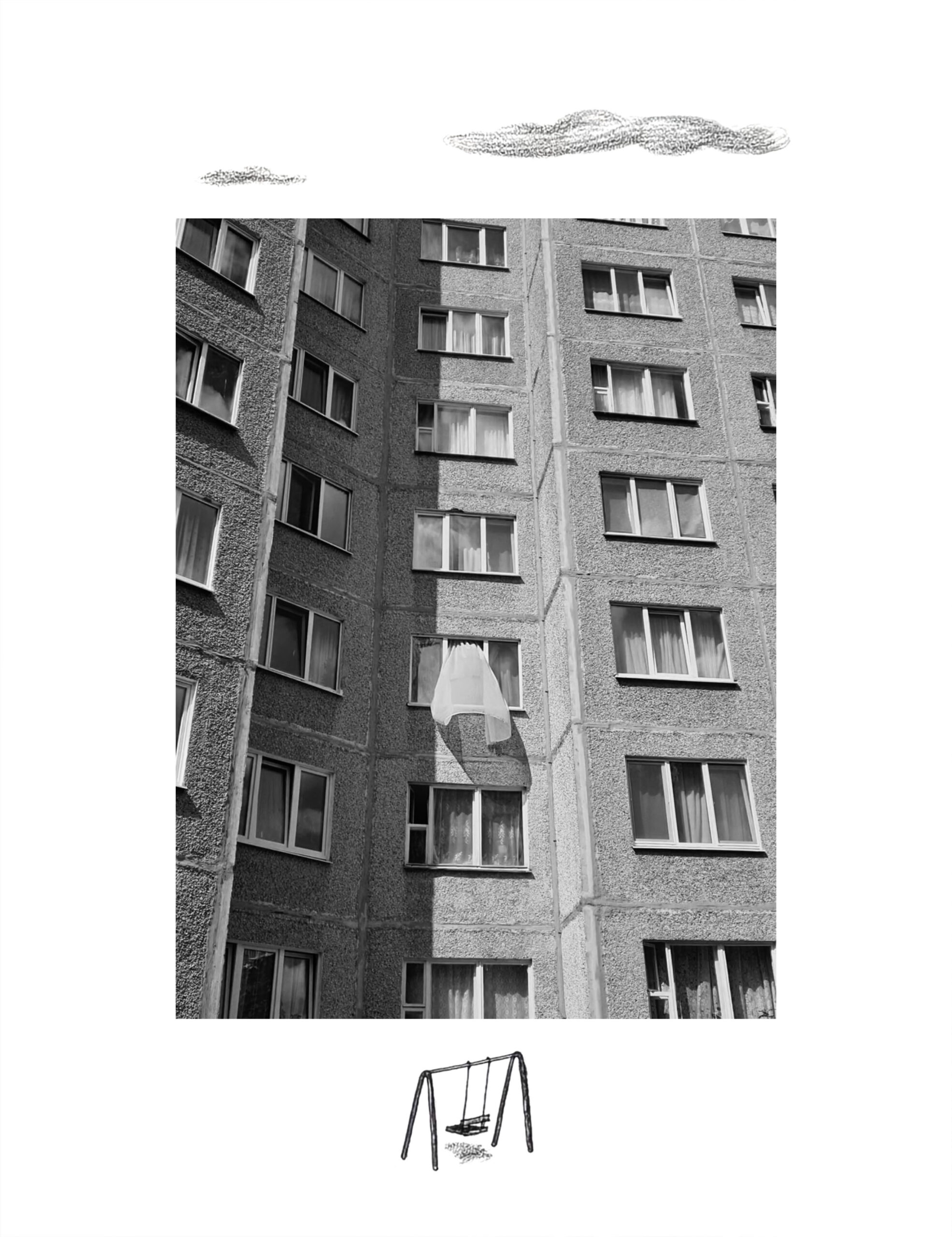

Can a drawing take us back to a place we can no longer reach — to the stairwell of our childhood, where the doors used to creak, to the courtyard where we made our first friends, to the home that now feels so far away? Perhaps this kind of teleportation is exactly what one experiences when looking at Liza Khikhlushka’s series of Belarusian panel buildings. This year, the artist announced the completion of her most emotionally resonant series — drawings of the homes of Belarusians living in emigration. On this occasion, we spoke with Liza about why the memory of home is more than just architecture — and how drawings can become a way to return.

Can a drawing take us back to a place we can no longer reach — to the stairwell of our childhood, where the doors used to creak, to the courtyard where we made our first friends, to the home that now feels so far away? Perhaps this kind of teleportation is exactly what one experiences when looking at Liza Khikhlushka’s series of Belarusian panel buildings. This year, the artist announced the completion of her most emotionally resonant series — drawings of the homes of Belarusians living in emigration. On this occasion, we spoke with Liza about why the memory of home is more than just architecture — and how drawings can become a way to return.

SHARE:

«In one of the drawings, I even included a dinosaur»

— How did the idea for this series come about? Do you remember the moment when you first decided to draw someone’s “special place”??

— I started this series in 2021, at a time when I was exploring the idea of a "portrait of home" — something deeply familiar to every resident of Belarus. I created a triptych called “I Am Home”, which brought together all the cultural symbols that evoke a sense of local identity — a collection of elements ranging from characters in Chagall’s paintings to a can of condensed milk, all enclosed within the outline of a house. That’s when I started reflecting: what exactly is “home” to me? Is it the building itself, the courtyard, the shop around the corner? And what is it for others?

In 2021, many people were leaving the country, and most of my audience was already living abroad. The themes in my work resonated especially strongly with those who had left but were longing for home. My drawings became associated with something familiar and stirred up personal memories. That’s when I decided to go deeper into personal experiences and announced the project on Instagram.

At the time, I was still in Minsk, so I had access to places that many in emigration could no longer reach. I created these works not only for those who couldn’t return to their hometowns, but also for those who wanted to revisit a period of life they could never return to. These drawings are filled with a sense of nostalgia and the impossibility of going back to that cozy past — even if that place is technically still in the same city as you.

— What was the process like: did people tell you about the place, send photos — and then what? Did their stories ever change your initial vision?

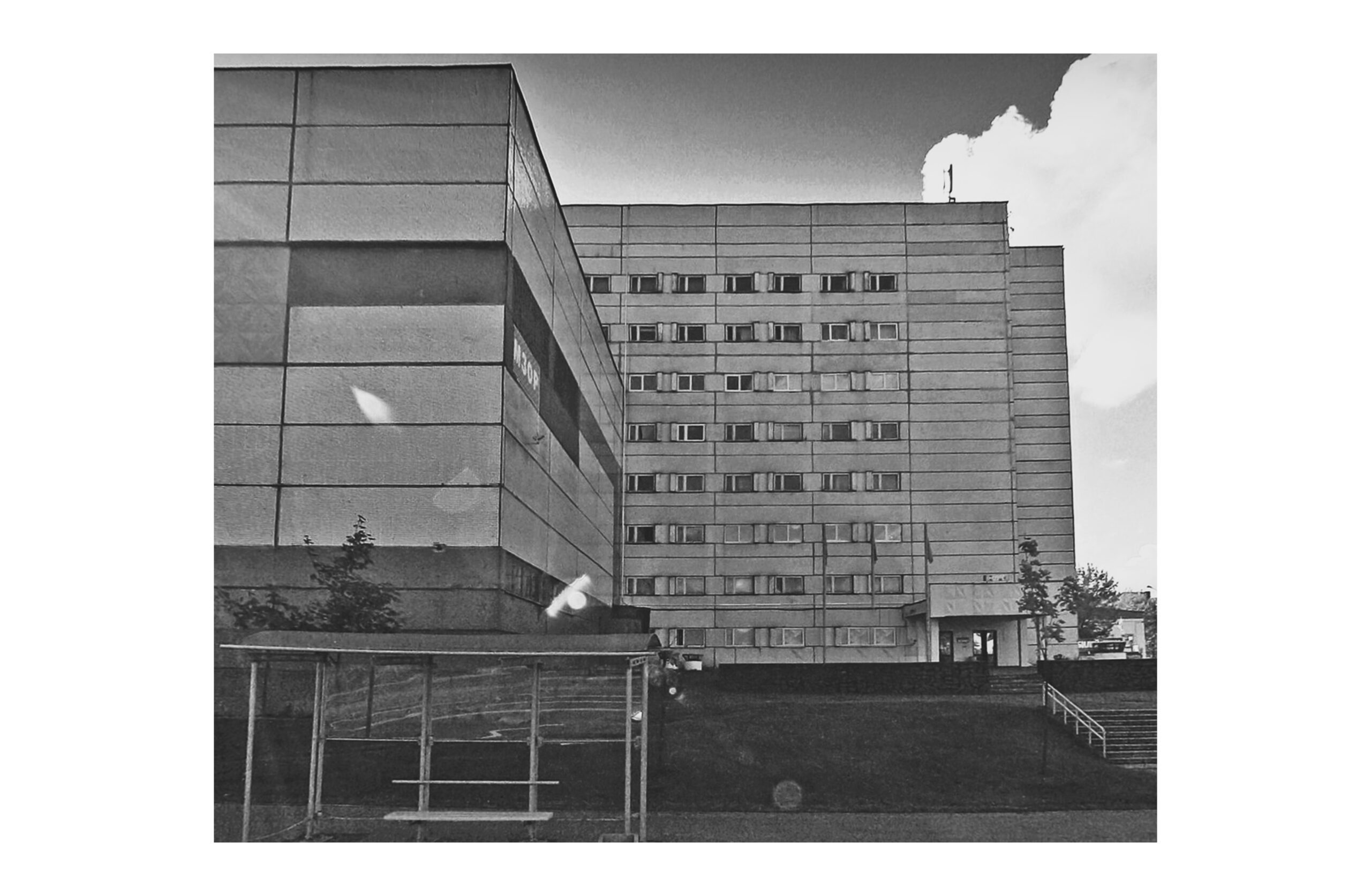

— Yes, people would describe the place in detail — its features, the emotions it evoked, and why it was meaningful to them. I asked them to send photos, and sometimes they even gave me the exact address. If it was in Minsk, I’d go there myself to explore the location or the building.

The descriptions were often very detailed: the architectural features of the building, the layout of the courtyard, the nearby shop, the games they played there, where they kept their sleds, what the view from the window looked like — even the smells.

«In one of the drawings, I even included a dinosaur»

— How did the idea for this series come about? Do you remember the moment when you first decided to draw someone’s “special place”?

— I started this series in 2021, at a time when I was exploring the idea of a "portrait of home" — something deeply familiar to every resident of Belarus. I created a triptych called “I Am Home”, which brought together all the cultural symbols that evoke a sense of local identity — a collection of elements ranging from characters in Chagall’s paintings to a can of condensed milk, all enclosed within the outline of a house. That’s when I started reflecting: what exactly is “home” to me? Is it the building itself, the courtyard, the shop around the corner? And what is it for others?

In 2021, many people were leaving the country, and most of my audience was already living abroad. The themes in my work resonated especially strongly with those who had left but were longing for home. My drawings became associated with something familiar and stirred up personal memories. That’s when I decided to go deeper into personal experiences and announced the project on Instagram.

At the time, I was still in Minsk, so I had access to places that many in emigration could no longer reach. I created these works not only for those who couldn’t return to their hometowns, but also for those who wanted to revisit a period of life they could never return to. These drawings are filled with a sense of nostalgia and the impossibility of going back to that cozy past — even if that place is technically still in the same city as you.

— What was the process like: did people tell you about the place, send photos — and then what? Did their stories ever change your initial vision?

— Yes, people would describe the place in detail — its features, the emotions it evoked, and why it was meaningful to them. I asked them to send photos, and sometimes they even gave me the exact address. If it was in Minsk, I’d go there myself to explore the location or the building.

The descriptions were often very detailed: the architectural features of the building, the layout of the courtyard, the nearby shop, the games they played there, where they kept their sleds, what the view from the window looked like — even the smells.

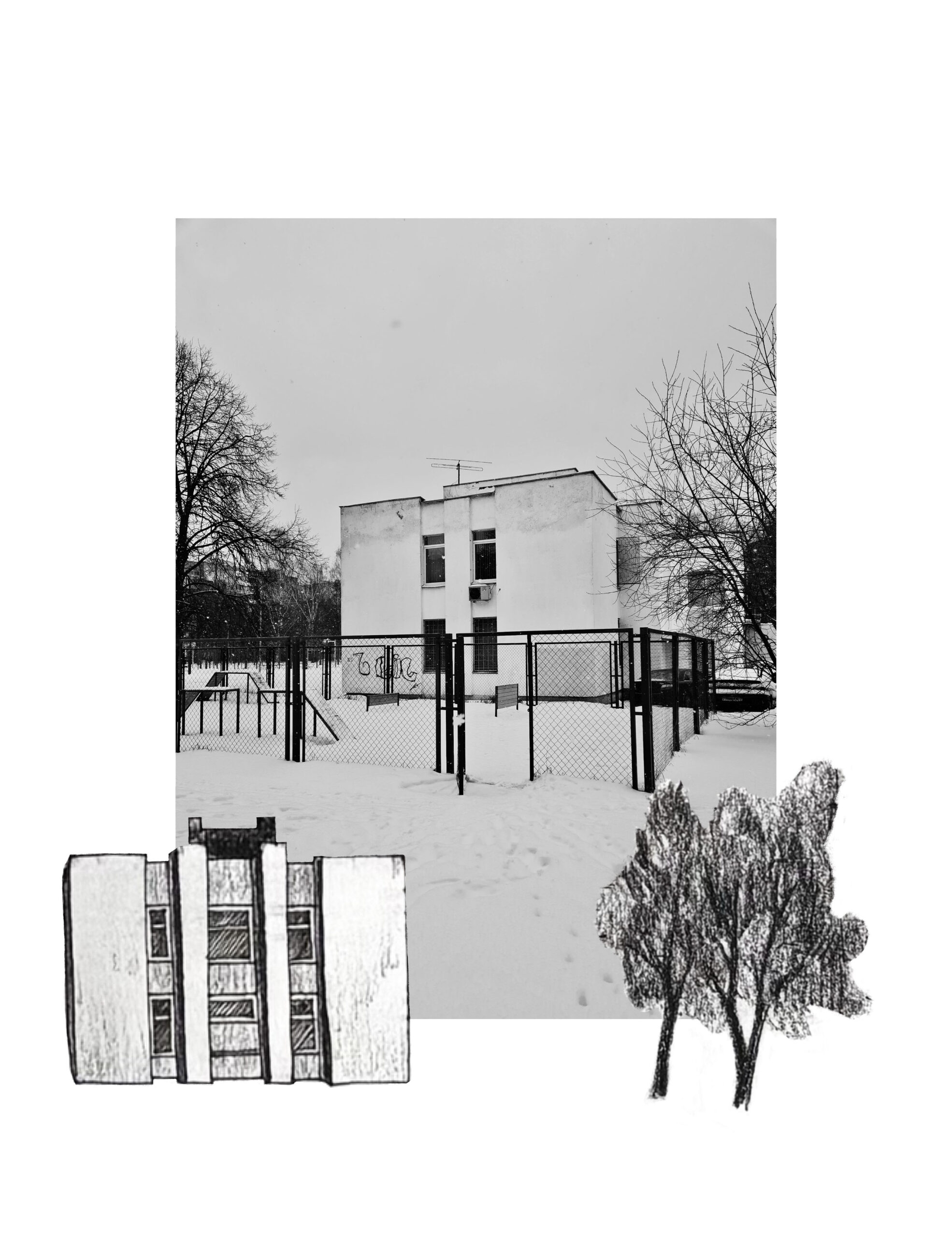

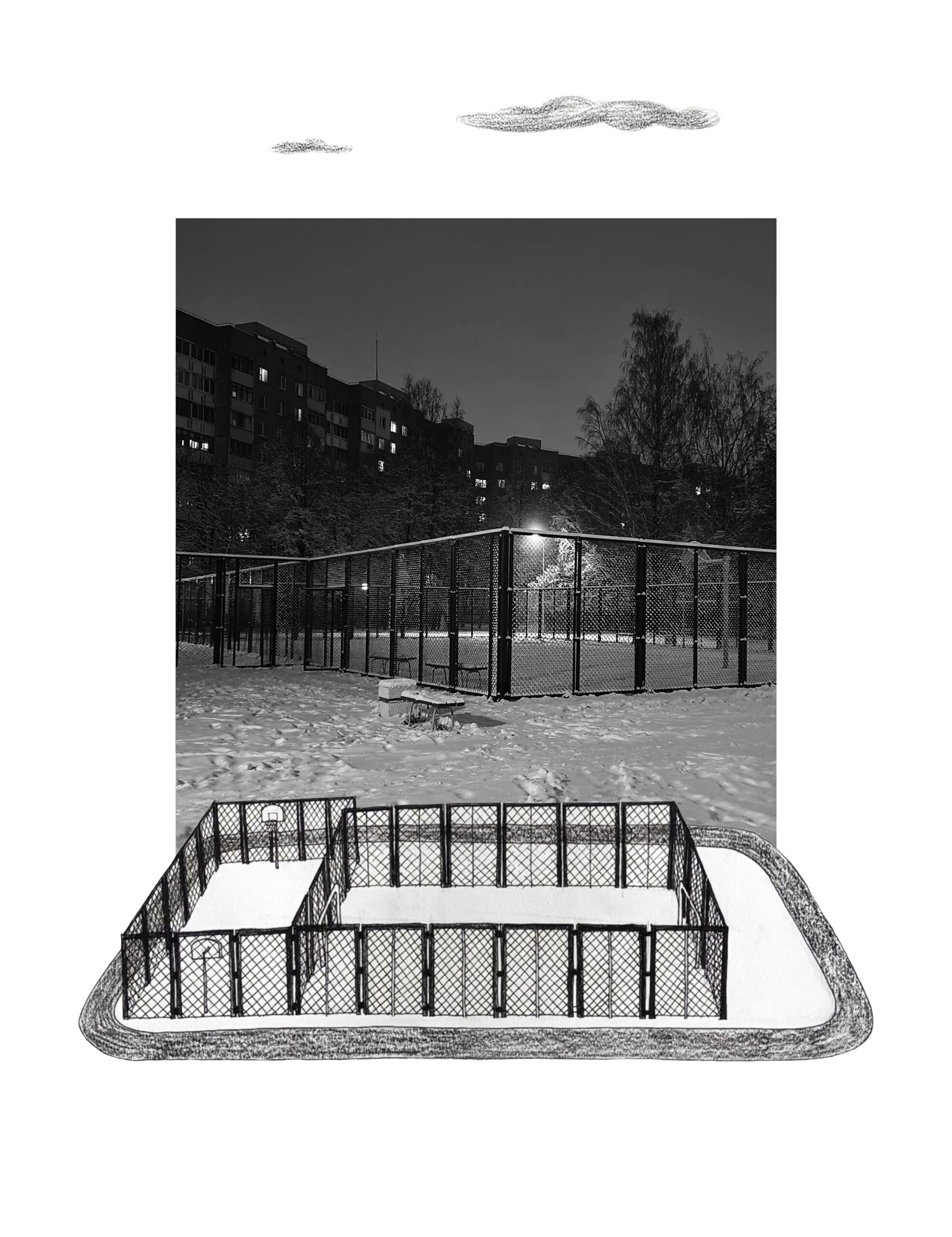

Sometimes I had to dig up archival photos because the building’s facade had changed, but the client wanted to see the house exactly as they remembered it. I was often asked to add elements that triggered personal memories — a cat, a tree, a swing — and in one of the drawings, I even included a dinosaur.

One of the most memorable commissions for me was a house in Svetlahorsk. The challenge was that there were no photographs, only an address, and it wasn’t possible to ask someone from there to take pictures. So I had to get creative: I used architectural blueprints of standard housing types, satellite views from Google Maps, the client’s own descriptions, and even a photo by Kasia Palasatka that happened to show the corner of the building. Piece by piece, the client and I managed to reconstruct a complete image of the house. I’m grateful for my architectural education — it really helped!

I would only start sketching after a full discussion with the client, so there were rarely any surprises. Although once, I did accidentally go to the wrong address and sketched the wrong building. But since it was only a draft, it was easily fixed.

— What did you feel while drawing someone else’s “home”?

— It’s a strange and moving feeling when someone lets you into something so deeply personal and trusts you to capture it — even though my perception of that place might be completely different, and that could influence how I draw it. I felt a responsibility not to miss the important details, and to simplify only what was truly insignificant.

I never aimed to replicate the landscape exactly; instead, I portrayed memories and associations. And as we know, memory is imperfect — so in my drawings, I layered the client’s interpretations over reality, rather than simply reproducing it.

— Has your connection to Minsk changed over the course of working on this project?

— A lot has changed since I started. I created the last piece in 2022. The year 2023 was very unstable for me — I was constantly on the move and didn’t have a stable space where I could fully commit to commissions like these. I also stopped mentioning the project on Instagram. It feels somewhat dishonest to continue it while no longer living in Belarus.

While I was still in Minsk, all of these works filled me with a pure warmth, without any hint of sadness. But in 2023, while living in Paris, I created a series dedicated to Minsk, which eventually became an exhibition at the “Marks” bookstore. That series was more about longing and pain — for a place that will always be home to me, but that I can no longer access the way I once could.

I increasingly notice how I’m becoming more distant from the city. To truly belong there, you have to be present — to know which new cafés have opened, what color the swings in the courtyard have been painted.

It's hard for me now to create new works about Minsk. I feel it less and less. I'm no longer immersed in its visual environment. And beyond that, any attempt to work with the theme of Minsk now only brings up a sense of pain.

«Well, now I’m here too»

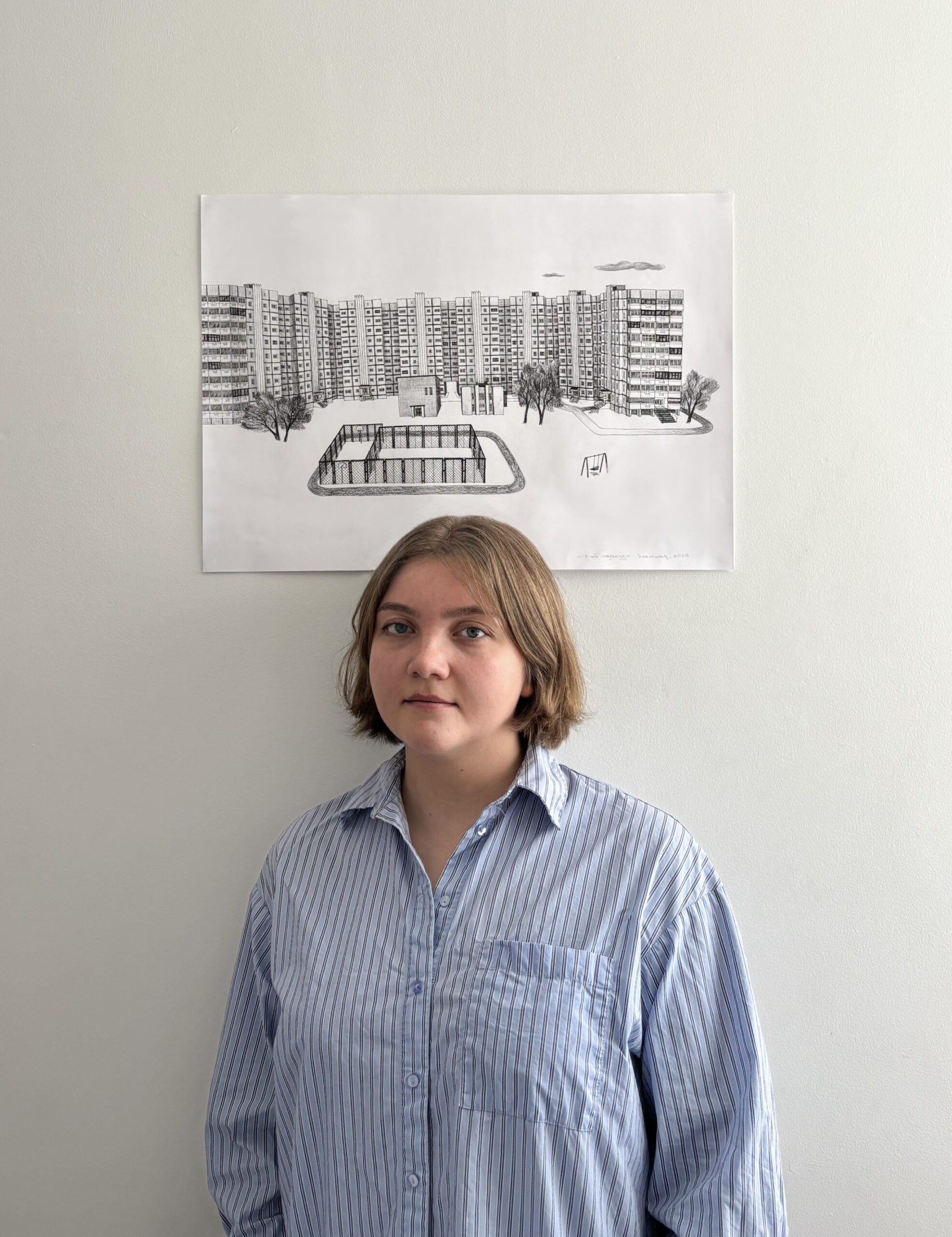

— Why did you decide to end the series with your own home? What did you feel when you drew it?

— I remember the moment I thought about these works again — it was in March of this year — and I thought, “Well, now I’m here too.” Now I’m also in emigration, just like the people who once so warmly shared stories of their hometowns with me.

Even though I’ve been living in London for over a year now, I still experience waves of longing for Minsk — and I doubt that feeling will ever completely go away. But during one of those tough moments, the idea came to me to draw my own home — as a kind of therapeutic act. Maybe it would help me let go?

I’ll say right away: no, I didn’t “let go,” and it didn’t exactly make me feel better. But the drawing became incredibly precious to me — it’s a small piece of home that I can now take with me wherever I go.

I drew the house and courtyard from my childhood — the same place where my parents still live. I didn’t really have any photos. Sure, I could’ve asked my parents to send some, but I didn’t need to — I remember every corner in vivid detail. So, using only memory sketches and Google Maps (I had to double-check how many entrances the building had, and the layout of some elements), I recreated my place.

It was difficult — much more than I expected. I had to take long breaks; I just couldn’t continue drawing. The sadness only deepened as I worked. And yet, technically, I can still go back — yes, it’s long and complicated, but my parents and cat still live there. Still, I don’t feel like I belong to that place anymore.

I never had the need to draw something like this for myself while I was living in Minsk, because I could always just go there. Now, everything’s different. I can’t continue this series while living in emigration, because the whole idea was based on me being here, in Belarus — while the people I was drawing for were no longer here. When I was in Minsk, I had “access” to their memories. But after I left, continuing the series lost its meaning.

Ending the series was emotionally hard. I felt like drawing my own home was a symbol — a marker of the end of a certain reality. The reality in which I was an artist living in Minsk, creating work about Minsk and Belarus.

I never wanted to let go of that reality — it’s where I’ve always felt most authentic. But circumstances changed. Of course, I can still keep working with this theme, but it will likely come from a different perspective now.

Liza Khikhlushka with a drawing of her home — the final piece in the series / 2025.

— How did moving to London affect your perception of this series?

The move made me realize that I now exist in a completely different reality from the one I lived in during 2021–2022, when the series was being created. Now I find myself in the same position as the people who used to commission drawings of their memories from me. And maybe… I need one of those drawings too?

I only allowed myself to think about this almost a year after moving to London. Before that, I was trying to make sense of this new reality — to feel it out, to sketch it in my works. I was looking for something that would resonate with me the same way a crooked concrete fence in Minsk once did.

I really like London’s aesthetic — its imperfect charm, the graffiti, the red brick, the contrast between skyscrapers and little two-story houses. I don’t feel like it’s truly mine yet, but at least it’s become familiar.

— Are there any drawings from the series that still feel especially close or emotionally resonant to you?

— One drawing gave me a persistent feeling that I was painting my grandparents’ yard and building. It was the same type of five-story Soviet apartment block, with a birch grove in front of the entrances, the same classic playground slides and swings.

In moments like that, you become acutely aware of how much standardized architecture shapes our shared sense of memory and place.

«Home in my work is not just an urban landscape»

— Do you plan to exhibit this series? Have you shown it anywhere before?

— In fact, this series only exists in full form in a folder on my computer. The main goal of creating these works was to give people a way to carry a piece of something familiar with them through my art. So aside from the drawing of my own home, I don’t physically have any of these works anymore.

For example, the drawing of the house in Svetlahorsk had quite a journey: I initially sent it to the client in Kyiv, but when the war started, the painting remained there. Eventually, though, they were reunited. The artwork fulfilled its purpose.

— Do you want to continue exploring the themes of home, memory, and personal space in new projects?

— Yes, absolutely. Right now, as someone living in emigration, these are the main themes I reflect on. In fact, the concept of "home" has been central to my work from the very beginning of my artistic journey.

During my studies in Poland (2018–2021), I was often filled with longing and questions about where exactly I belong — where is the place I can truly call home? When I returned to Minsk in 2020 due to the pandemic, I started taking my art practice more seriously, using it as a way to explore the phenomenon of home — its cultural, emotional, and architectural layers.

I’m deeply interested in how architecture and urban planning shape our sense of home, belonging, and identity. In my work, “home” isn’t just a cityscape — it’s a layered image built from memories, personal emotions, and cultural context.

Now, living in London, I’m searching for visual and emotional elements that can help me create a new sense of home here.

— What do you hope people feel when they look at your drawings from the series?

— Each drawing was created specifically for the person who requested it — they were meant only for them. I hope these works bring people a sense of home, even just a small piece of it. And I hope they don’t stir too much sadness, but instead let warm memories surface.

Lizaveta Khikhlushka is a Belarusian illustrator and graphic designer well known to the Belarusian audience for her numerous collaborations with local brands and a graphic series of Belarusian panel houses.

The artist specializes in creating vibrant illustrations and designs for various purposes, including fashion prints and textile patterns, packaging, visual content for digital platforms and brand identity. Lizaveta's clients include Flo, Mark Formelle and LUCH.

The artist currently lives and works in London.

Lizaveta Khikhlushka is a Belarusian illustrator and graphic designer well known to the Belarusian audience for her numerous collaborations with local brands and a graphic series of Belarusian panel houses.

The artist specializes in creating vibrant illustrations and designs for various purposes, including fashion prints and textile patterns, packaging, visual content for digital platforms and brand identity. Lizaveta's clients include Flo, Mark Formelle and LUCH.

The artist currently lives and works in London.

SHARE:

Чытаць таксама:

FOLLOW US

INSTAGRAM TELEGRAM TIKTOK FACEBOOK YOUTUBE

© Chrysalis Mag, 2018-2025

Reprinting of materials or fragments of materials

is allowed only with the written permission