From Utopia to Vulnerability: the Female Body in Belarusian Art of the 20th-21st Centuries

The Line | Analytics, 19.11.2025

“The Line” project continues with an analytical piece by Volia Davydzik. Exclusively for the journal, she unpacks how the image of women in Belarusian art has shifted - from the BSSR period to today. Through specific examples, we explore nearly a century of artistic evolution and ask ourselves: can we draw an unbroken line of female presence in Belarusian art?

SHARE:

Introduction

While researching the genealogy of the female image in the art of the BSSR and the post-Soviet period, I encountered an absence of material from the 1930s-1950s. Women artists of that time remain almost invisible: their names are seldom mentioned, many of their works are lost, and their perspectives on femininity never had a chance to form a distinct artistic tradition.

This is a story of double — if not triple — erasure. Political and institutional systems placed women artists at the margins, confining them to the suffocating label of “women’s art”. At the same time, social expectations and domestic labour made them secondary to their husbands and fathers. To make matters worse, forced emigration and internal repressions wiped out many names entirely from the history of Belarusian art. As a result, countless biographies were disrupted, and artistic legacies were either appropriated by other contexts or destroyed altogether.

The situation began to shift in the 2000s. The earlier fragmentation and elusive presence of women artists gave way to a new generation. By employing radical practices and articulating the female body as a site of critique, memory, and resistance — within a still conservative and constrained cultural field — they began to claim their space.

However, this earlier fragmentation is itself a marker of power structures. It permeates every level - from the private lives of women artists to institutional precarity and even the artworks themselves. The female artist in Belarusian art remains an elusive figure, existing in a state of transit between larger systems.

In this text, I aim to turn that elusiveness into a research method — tracing the movement from the utopian image of the “socialist realist icon” toward the return of corporeality, and finally, toward the articulation of trauma and vulnerability.

Women’s Image Between Utopia and Everyday Life

Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, the image of women in Belarusian art was forged in a tension between utopia and lived experience. Within the Soviet canon, the female figure embodied collective ideals. In the painting and monumental art of the BSSR during the 1930s-1950s, a vision of the future prevailed — one stripped of individuality and bodily concreteness.

The Bolshevik project of women’s emancipation, articulated by Kollontai and other feminists of the 1920s, quickly faded. By the 1940s, patriarchal norms had reasserted themselves: women carried a double burden of labor and home, and endured the trials of war, displacement, and repression. Official art responded with heroization — turning female figures into symbols of sacrifice and strength. Yet beneath this idealization simmered a quiet dissonance between lived experience and artistic representation, one that occasionally surfaced as latent tension and found expression in alternative artistic practices.

Yudel Penn — "Portrait of Elena Kabischar-Yakerson"

Utopia and Cracks in the Official Canon (1930s-1960s)

The analysis of the 1930s-1950s follows three lines of rupture: the official canon, its disruption through avant-garde practices, and intimate strategies where the bodily and personal emerge.

Raisa Kudrevich's “In the Native Kolkhoz” (1955), with its transparent colors and dynamic composition, positions women at the center of action — as embodiments of happiness in communal life. There is no sign of fatigue or suffering here, the heroines’ bodies are translated into the language of utopia, and their images serve as mediums of ideology. The work captures the paradox of socialist realism: everyday scenes are transformed into metaphors of communal life, with female presence serving the imagined future.

Raisa Kudrevich, In the Native Kolkhoz / 1955

Vera Ermolaeva’s “Woman with a Child” (1933) stands out as a striking example of the canon’s subversion. An avant-garde artist and UNOVIS member executed in 1937 for “anti-Soviet activity”, she interprets the Madonna archetype within a heavy, grounded scene of everyday life. Both mother and child are depicted roughly, solidly, and facelessly. The compressed space and thick paint create a sense of confinement and weight. Here, motherhood is not a symbol of the future but a lived experience of flesh, fatigue, and despair. Ermolaeva makes visible what the canon represses, turning the female body into a site of tension and vulnerability.

Vera Ermolaeva, Woman with a Child / 1933

The third line of ruptures is found in more intimate, cameral works. In her “Self-Portrait” (1941), painted during the siege of Leningrad, Eugenia Magaril presents herself stripped of any symbolic weight. Rather than a “woman-icon”, she portrays a figure that asserts personal presence and her own gaze. Her austere and restrained depiction demonstrates the possibility of another visual language — one in which women are subjects, not symbols..

Eugenia Magaril, Self-Portrait / 1941

Even under the dominance of socialist realism — refracted in BSSR through local utopias and the figure of the “woman-icon” — the cultural field was far from monolithic. Ruptures, alternative visual languages and images appeared within it, undermining the fanaticism of power, as well as complexing and transforming the representation of women.

From Image to Strategy: Tactics of Presence and Institutional Barriers (Litvinava, Rusava, Sazykina)

During the 1970s-1980s, artists Zoja Litvinava, Liudmila Rusava, and Volha Sazykina employed distinct strategies to enter and establish themselves in the art field, which remained deeply hierarchical and institutionally male-dominated.

Belarusian artists Zoja Litvinova, Liudmila Rusava and Volha Sazykina.

For Litvinava, one of the pioneering women in monumental art, navigating and overcoming barriers to recognition was crucial in an environment marked by gender bias and the marginalization of women. Rusava, in contrast, distanced herself from the very category of “women’s art”, stating “A good work is one where I can’t tell it was made by a woman”. This reflects her effort both to resist the reduction and exoticization of artistic practice based on gender and to assert an autonomy of her artistic voice.

Sazykina, in turn, emphasized materiality, employing handmade paper, sand, organic fibers, and hair as media of memory and bodily experience. Through this, she transformed the corporeal into the artistic, creating a space where materiality itself became a form of resistance to the canon.

Overall, rather than representing the development of “female images”, the practises of Litvinava, Rusava, and Sazykina were more about claiming presence and asserting value in a field that persistently erased and devalued women’s artistic contributions.

Ludmila Rusova, After, performance,1997, The 6th Line gallery, Minsk. Photo by U. Jurcanka. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xJ04na0Tuzw / photo taken from secondaryarchive.org

Litvinava’s “Blooming” (1988), as described by the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus, embodies vitality, fertility, and motherhood. In the context of the 1980s Belarusian art scene, it marks a shift from heroic, iconic representations of women toward a more intimate, decorative metaphor. The painting’s female figures are drawn not from socialist utopia but from archetypal origins connected with nature and the life cycle. Despite its vivid color palette, originality, and emotional richness, the work remains within the realm of symbolic generalization, where the female body is not individualized but functions as a symbol of generative power. Blooming captures a transitional moment from the utopian canon, reaffirming the traditional “mother-nature” archetype. Litvinava’s strategy asserts female presence in the art field via a “safe” theme — one that enables the articulation of a “female gaze” while not fully allowing personal experience.

Zoja Litvinava, Blooming / 1988

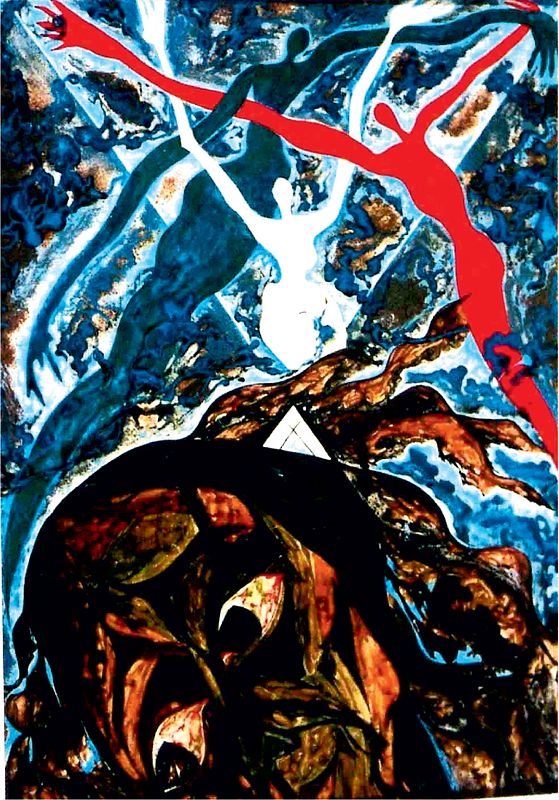

Rusava’s “Composition” (ca. 1988) presents a different vision — one built on sharp contrasts. In the upper section of the work, three elongated figures reach upward against an almost cosmic backdrop. Their movements are bound by rhythm, forming a kind of a geometric dynamism. The bodies are abstract, devoid of individuality.

At the bottom, a heavy, dark face with wide-open eyes and hair resembling roots stretches upward, capturing a sense of pain, fear, and trauma. Rusava renders the body as a site of radical tension — at once vulnerable and striving toward liberation. Instead of heroism or a readily legible symbol, we encounter motion, impulse, suffering, and resistance. She transforms the body into a space of extreme experience — not iconic but anonymous, wounded, and yearning for freedom — where the female figure emerges as an energy of endurance and transcendence.

Liudmila Rusava, Composition / ca. 1988

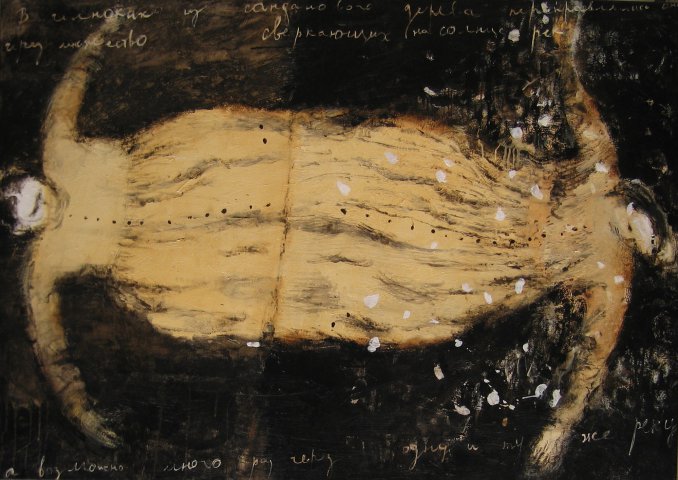

Volha Sazykina’s artistic practice also stands apart from the official canon of Belarusian art of the period. Moving beyond the confines of easel and decorative art, she adopted strategies that occupy a kind of “third space”, where female experience could be articulated without reducing it to iconography or utopia. Her works function as mediums of critical expression, through which the uncertainty of everyday existence emerges.

This approach is most vividly embodied in her “Existence” (ca. 1980s). Here, a pair of women’s shoes serves as soil for grass to grow. The female body is rendered through absence, and the shoes become a metaphorical trace — a vessel capable of giving birth to something new. The contrast between the organic and the artificial, the fragile ecosystem and the coarse material, exposes the contradictions of female experience in the late Soviet era: existence poised between vulnerability and resilience, invisibility and ongoing creation. In “Existence” Sazykina depicts neither a heroine nor a symbol but a mode of survival — a life process in its simplest, everyday form. The work gestures toward a new mode of articulating female presence: not through an icon or utopian image, but through traces, through growth that pushes out from within and between structures — with its own voice and capacity to endure.

Volha Sazykina, Existence, ca. 1980s

Women’s Image as Critique and Experience: New Strategies of the 2000s

The 2000s in Belarusian art mark a rupture with post-Soviet inertia and a search for new artistic languages. During this period, women’s practices established a distinctive field in which the image of women is no longer secondary to patriarchal canon, but acts as an independent critical lens. Several strategies emerge within this field. Foremost among these is a focus on corporeality and vulnerability, in which the body ceases to be an archetype and becomes a medium of lived reality. Simultaneously, a strategy of deconstructing the language of power develops, employing women’s perspectives to expose mechanisms of propaganda, masculine discourse, and identity normalization.

Equally significant is the strategy of memory, where female presence is expressed not through completed symbols but through traces, fragments, or imprints. Directly connected with historical invisibility and trauma, it creates a tactic of intimization, turning forms, gestures, and spaces into carriers of personal and everyday experience, countering “grand narratives” and utopian promises. In this context, a new generation of female artists emerges, directly or indirectly aligned with feminist strategies, asserting the autonomy of female experience and forging new collective modes of existence in art.

Marina Naprushkina, Office for Anti-Propaganda / 2007 – 20012 / image from the artist's website.

In her 2006 work “Mother-Heroine”, Antanina Slabodchykava engages with the image of the Soviet woman, breaking it into fragments. The female body becomes visible — not as a whole, through ruptures revealing the violent nature of the image itself. Slabodcykava’s artistic practice in the 2000s revolves around critically rethinking the female image and the mechanisms of its institutional representation. Through this painting, she confronts the widely circulated Soviet depiction to radically deconstruct it using collage technique. Fragmentation and montage dissect the construction of “woman-icon” created by the socialist realism canon. Instead of a coherent image of heroic utopia, we see a tense interplay of dissonant elements, where corporeality and assigned role no longer align.

In doing so, Slabadchykava exposes not only the anachronistic but also the violent nature of the structure that confines the female body to its function alone, depriving it of any autonomy. Collage becomes a tool of deconstruction, exposing the mechanisms behind the image-making and restoring the figure’s contradictions, vulnerability, and fragmentation. Her strategy relocated the image of women from the symbolic plain to a site of critical experience, allowing subjectivity to emerge through rupture and incommensurability instead of wholeness.

Antanina Slabodchykava, Mother-Heroine / 2006

In her series Inciting Force (2011-2020), Zhanna Gladko revisits one of the most iconic gestures of avant-garde cinema: the eye-slitting scene from Bunuel and Dali’s film “Un Chien Andalou” (1929). In its original context, this act symbolized a break from bourgeois rationality and a rejection of a gaze that structures, orders, and categorizes the world. The violent destruction of the eye opened a space for the irrational, chaotic, and ungovernable. Gladko reinterprets the gesture, shifting its meaning.

Her portraits depict women in aestheticized, theatrical forms, drawing on elements of classical and glossy visual codes. In “Untitled” (2014), a line across the eyes marks the potential moment of slitting, yet the act remains incomplete. Unlike Bunuel and Dali, who erased the subject's ability to see with the gesture, Gladko preserves the gaze, and turns it into a point of intense focus. Her subjects continue to look despite the danger. The work exposes the gendered dimension of the gesture itself: while the original act in “Un chien andalou” implied liberation from the order of symbols, in Gladko’s female reinterpretation, this liberation is unresolved, suspended in tension and uncertainty. The violin act is reversed: rather than disappearing, the female subject claims her vision. The female gaze is not nullified but reclaimed as a space of resistance, maintained even under threat of destruction.

Zhanna Gladko, Untitled (2014) from the series Inciting Force / 2011-2020

Natalia Zaloznaja’s Little World series (2009-2010) transforms the body into a figure of precarious balance. Rather than depicting female presence as a conventional image, the series presents it as a mode of existence within a confined space. She develops a sculptural language in which figures are depicted in a state of being. The silhouettes lack individuality yet retain palpable corporeal tension. They are elongated and frozen in the moment, maintaining a balance between movement and stillness. The “small world” emphasizes not universal order but the fragility of individual existence, its limitations, and a focus on internal states. An effect of intimization emerges, drawing attention to micro-experiences, gestures, and poses that resist fixed or clear interpretation. Through rhythm and plasticity, the figures convey a sense of maintaining equilibrium under external pressures.

Natalia Zaloznaja, Little World / 2009-2010

Afterword

The evolution of the female image in Belarusian art of the 20th-21st centuries is not a story of linear development, but one defined by constant tension: between body and its image, canon and its subversion, political utopia and personal experience. The image of women shifts from utopian icon to corporeal embodiment, yet this transformation reflects not only changes in visual strategies, but also the struggle for women’s visibility, including that of female artists. Moving from peripheral presence to establishing their own voice and critical field for expression, women’s art becomes more than an illustration of social changes — it emerges as an independent force shaping new forms of existence, articulating memory, vulnerability, and resistance.

Volia Davydzik is a researcher, philosopher and lecturer, a PhD student in the “Cultures of Critique” program at Leuphana University (Germany).

In her dissertation, she explores protest art, practices of care and solidarity in the Belarusian context after 2020, drawing on feminist philosophy, anarchist theory, social criticism and cultural approaches. Her research interests include feminism, post-Soviet transformations, theories of affect and reproductive labor, and artistic practices in exile.

Volya has been published in Digital Icons, Moscow Art Magazine, Topos, and in international exhibition catalogs. Recently, she has been actively presenting on the topics of revolutionary care, cyberfeminism, and exile at academic and public events in Europe.

In addition to her academic work, she collaborates with independent curatorial and activist initiatives focused on memory, trauma, and visual forms of resistance.

Similar Materials

FOLLOW US

INSTAGRAM TELEGRAM TIKTOK FACEBOOK YOUTUBE

© Chrysalis Mag, 2018-2026

Reprinting of materials or fragments of materials

is allowed only with the written permission