Belarusian Voice in Jewelry Art: Elena Karpilova at Lisbon, Munich, and Venice Biennales

Belarusian Voice in Jewelry Art: Elena Karpilova at Lisbon, Munich, and Venice Biennales

Interview | 22.09.2025

Elena Karpilova’s name is not often heard in Belarusian media, although her jewelry and architectural-educational projects attract attention and receive warm recognition on both sides of the Atlantic. Elena is a curator, designer, author of international art publications, and co-founder of the School of Architectural Thinking – an outstanding project in informal children’s education. For 34mag, Palina Yurgenson spoke with the artist, who now lives in Portugal, about a field that practically does not exist in Belarus, about a home exhibition featuring kholodnik (cold beet soup) within the Lisbon Biennale, and about the historic participation of Belarusians in two consecutive Venice Biennales.

We republish the text of 34mag in Belarusian without changes and add its English translation.

Elena Karpilova’s name is not often heard in Belarusian media, although her jewelry and architectural-educational projects attract attention and receive warm recognition on both sides of the Atlantic. Elena is a curator, designer, author of international art publications, and co-founder of the School of Architectural Thinking – an outstanding project in informal children’s education. For 34mag, Palina Yurgenson spoke with the artist, who now lives in Portugal, about a field that practically does not exist in Belarus, about a home exhibition featuring kholodnik (cold beet soup) within the Lisbon Biennale, and about the historic participation of Belarusians in two consecutive Venice Biennales.

We republish the text of 34mag in Belarusian without changes and add its English translation.

SHARE:

First works, first publications

— How does one become a jeweler in Belarus?

— If we had a place offering jewelry education, I probably would have started directly as a jeweler. But jewelry as a structured field does not exist in Belarus, especially contemporary jewelry with its own style, or even as an evolving art form. Because of this, for a long time I imagined myself as a classical artist – completely detached from the present.

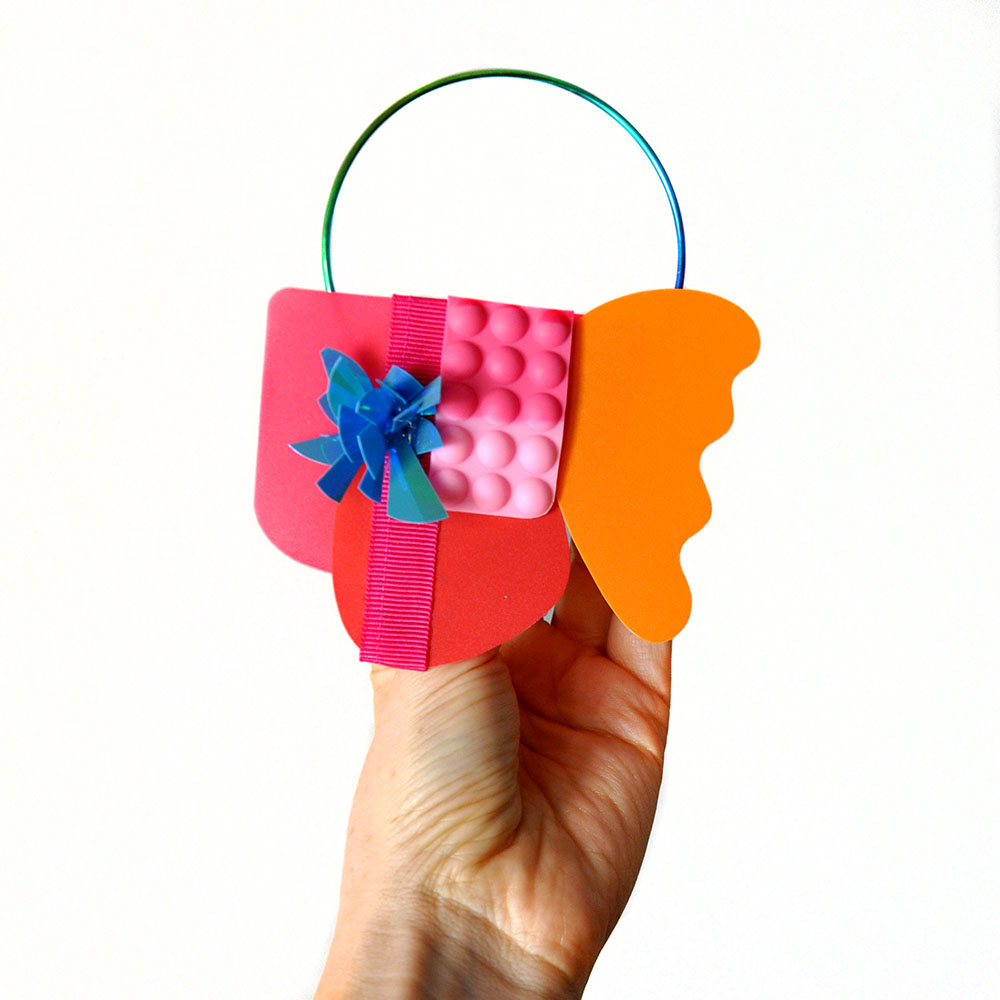

But I began making small decorations from polymer clay, which I brought from Lithuania, back in 2006. At that time, I also started bringing my colorful, playful pieces to Padzemka, which was run by Hanna Chystaserda and Valyantsina Kisialova [later – founders of the “Ў” Contemporary Art Gallery. – ed. note 34]. And they even sold! It was a student side job, and all the profit went, naturally, toward paints, because I was studying painting.

Over time, I started taking jewelry more seriously, reading the main international resources on the subject. I recall this with a smile. Life is funny: once I began as a reader of Art Jewelry Forum – the world’s leading online publication on contemporary jewelry – and now I am one of their authors.

I write for different jewelry media and work on various projects. In July, a quest project for children, created with my colleague Into Niilo, will be released for the Antwerp Diamond Museum DIVA. In mid-June, I served as an invited jury member in Hasselt, Belgium, at the presentation of master’s works in Contemporary Jewelry. Right now, I’m writing three texts in parallel.

First works, first publications

— How does one become a jeweler in Belarus?

— If we had a place offering jewelry education, I probably would have started directly as a jeweler. But jewelry as a structured field does not exist in Belarus, especially contemporary jewelry with its own style, or even as an evolving art form. Because of this, for a long time I imagined myself as a classical artist – completely detached from the present.

But I began making small decorations from polymer clay, which I brought from Lithuania, back in 2006. At that time, I also started bringing my colorful, playful pieces to Padzemka, which was run by Hanna Chystaserda and Valyantsina Kisialova [later – founders of the “Ў” Contemporary Art Gallery. – ed. note 34]. And they even sold! It was a student side job, and all the profit went, naturally, toward paints, because I was studying painting.

Over time, I started taking jewelry more seriously, reading the main international resources on the subject. I recall this with a smile. Life is funny: once I began as a reader of Art Jewelry Forum – the world’s leading online publication on contemporary jewelry – and now I am one of their authors.

I write for different jewelry media and work on various projects. In July, a quest project for children, created with my colleague Into Niilo, will be released for the Antwerp Diamond Museum DIVA. In mid-June, I served as an invited jury member in Hasselt, Belgium, at the presentation of master’s works in Contemporary Jewelry. Right now, I’m writing three texts in parallel.

Elena Karpilova / photos from the personal page of the artist and author / 2025.

— What changed when you discovered international jewelry publications while still in Belarus?

— I very much wanted someone to teach me how to work with metal! But it turned out to be quite difficult in Belarus. I went to different jewelers, asked to learn, and received lots of refusals like: “Oh no, why would you need this? You’ll look for a day and never come back.” Now I understand that for jewelers, as for anyone with craftsmanship, it is important not only to teach for money but to continue the culture of apprenticeships.

So, I started working with plastic and alternative materials, and I created a personal Instagram page to share photos of my works, interesting pieces from other artists around the world, and things that inspired me. There was no profit from the blog – I simply wanted to share and learn.

— When did the personal blog grow into texts for major international media?

— In 2022. I thought a lot about how I could help my colleagues in Ukraine, and I came up with the idea of writing to the American website Art Jewelry Forum. I explained to the editor: “I understand that you don’t know me at all, but I would really like to do something useful for Ukrainian colleagues, support them, and give them a voice on the international stage by writing about them.” My idea was to publish the works of good jewelers on a platform read by everyone – including American collectors. Such promotion for artists affected by the war, on a site where people actually buy, mattered.

The editor-in-chief replied the very same day: “We were just thinking that we know absolutely no one in the Ukrainian jewelry scene. We’d be happy to accept your text.” That’s how I published my first photo essay – and I kept writing.

In fact, I had already published some texts back in Belarus in the magazine Mastatstva. But it was after the international publication that I started writing more and finally found my own theoretical voice in the jewelry field. Now professors, editors, and jewelers even ask me: “Lena, why didn’t you write earlier?”

I still write and create visual content for Art Jewelry Forum. The platform is open to anyone who wants to publish: every author goes through the same commission-based selection process – even the most famous theorists of contemporary jewelry. Three to four times a year they open submissions, and all applications are reviewed equally.

Elena Karpilova / photos from the personal page of the artist and author / 2025.

Small objects with big meanings

— What’s the situation with jewelry art in Belarus?

— Compared to neighboring countries, like Lithuania, which even has a festival of contemporary jewelry (Metalofonas), Belarus has almost nothing – zero. There are only a few individuals involved. For example, Darya Lutskevich and her brand Label D. She uses wood from a 5,000-year-old oak – a material rich in history and symbolism – and participates in international festivals. But moving the whole field forward alone, or with just a few people, is impossible. And contemporary jewelry art is about freedom, about creating objects with narratives. In Belarus, any sphere with such meanings and ideas is now complicated.

— Yet we do have artists who move from their usual field (say, painting) into jewelry, even if they don’t identify as jewelers. Why?

— Because the activity is accessible and enjoyable. A jewelry object can be made in a short time – a day, a week, a month – unlike sculpture or architecture, which require much more time and resources. With your own hands, you create a high-quality, beautiful piece that can be shown, sold, or exhibited. That’s very inspiring.

And it can be especially valuable for those who cannot afford large artworks at home. Let’s say I, in emigration, want to buy a piece by Nastya Rydlevskaya, but as an artist she often works in large formats – masks or paintings. How can I be sure I’ll be able to transport such a piece if necessary? That’s where Anastasiya’s brooches come in. They are small but deeply meaningful art objects.

Products by Elena Karpilova.

Biennale at home

— As part of the Lisbon Biennale, you created an exhibition about the experience of migration. How was the project born?

— When I moved to Portugal, I immediately began getting to know the local art scene, meeting artists and curators I already knew or had only read about. At the same time, I started traveling to Munich’s biggest jewelry art festival. That’s where Lisbon Biennale art director Marta Costa Reis announced the theme of the upcoming event: “political adornments.” We were acquainted, and I invited her for tea to discuss an exhibition idea that had just come to me.

I wanted to make an exhibition about forced migration, and after my pitch, the art director told me: “You don’t need to apply to the competition, you’re in – it will be an honor to have your project in the program.” That’s how L’étrangère was born.

I wanted to approach the theme as a curator, not just as an author. I did show one of my works, but that was not the focus for me.

— How did you choose the participants?

— I immediately knew whom I wanted to invite. These were jewelers who, at different times and for various reasons, were forced to emigrate from their countries. I knew most of them personally; with some, I only corresponded. Some were true stars in the field, but almost no one knew their biographies. I collected information about them and wrote directly: “I’m making an exhibition about forced migration. I think this somehow relates to you.” And the person would suddenly reply: “Yes, very much so, here is my story.”

Besides providing a jewelry piece for the exhibition, I asked each participant to write a story. That was a mandatory condition. But if the story was too personal, they could write an essay about forced migration in general. For example, there was a woman from Iran who has long lived in Germany, but she said at once that she couldn’t share anything personal because she still travels to Iran, where her relatives live. She wrote a beautiful abstract text.

Screenshot from Elena Karpilova's website page.

— And the exhibition took place at your home?

— Yes. When I presented the concept, I immediately said: “I want to host the exhibition at my home.” It wasn’t a requirement of the Biennale – it was my idea. I am an emigrant, and I live in a typical migrant apartment – rented, simple, modest. To speak about such a difficult subject as forced migration in a gallery with white walls would have been strange. That’s why it wasn’t just an exhibition, but more of an experience. People came, looked, talked, and I treated them to traditional Belarusian kholodnik (cold beet soup). It was a moment of genuine communication, not just a gallery show.

— Wasn’t it hard for you to work with such a theme, given your own relocation experience?

— No, my emigration was my choice. For example, one participant fled Yugoslavia during the 1990s war, with a six-month-old baby in her arms. That was real forced emigration. For me, it was interesting to learn the stories of others and work with them. It was mostly a professional experience.

— How did visitors react?

— Very well. People said it was unexpected, especially compared to other exhibitions. Imagine: they go around galleries, and suddenly they find themselves in a Belarusian migrant’s apartment, where everything feels homely. The contrast was strong. Visitors from very distant countries, like Australia or New Zealand, were especially struck. It wasn’t just an exhibition, but something new for them – immersion into someone’s personal stories and space. Something soulful, larger than an exposition.

Photo from Elena Karpilova's exhibition from her exhibition during the Lisbon Jewelry Biennale / 2025.

Telebridge

— How did the project get into the Munich Jewelry Week program?

— The organizers approached me themselves. They had been at my Lisbon home exhibition – and liked it. But presenting the project in Munich required resources, and a question arose immediately: if we’re doing the project, then how? I didn’t live there, I wasn’t a migrant renting an apartment in Munich. The whole concept needed to be reworked.

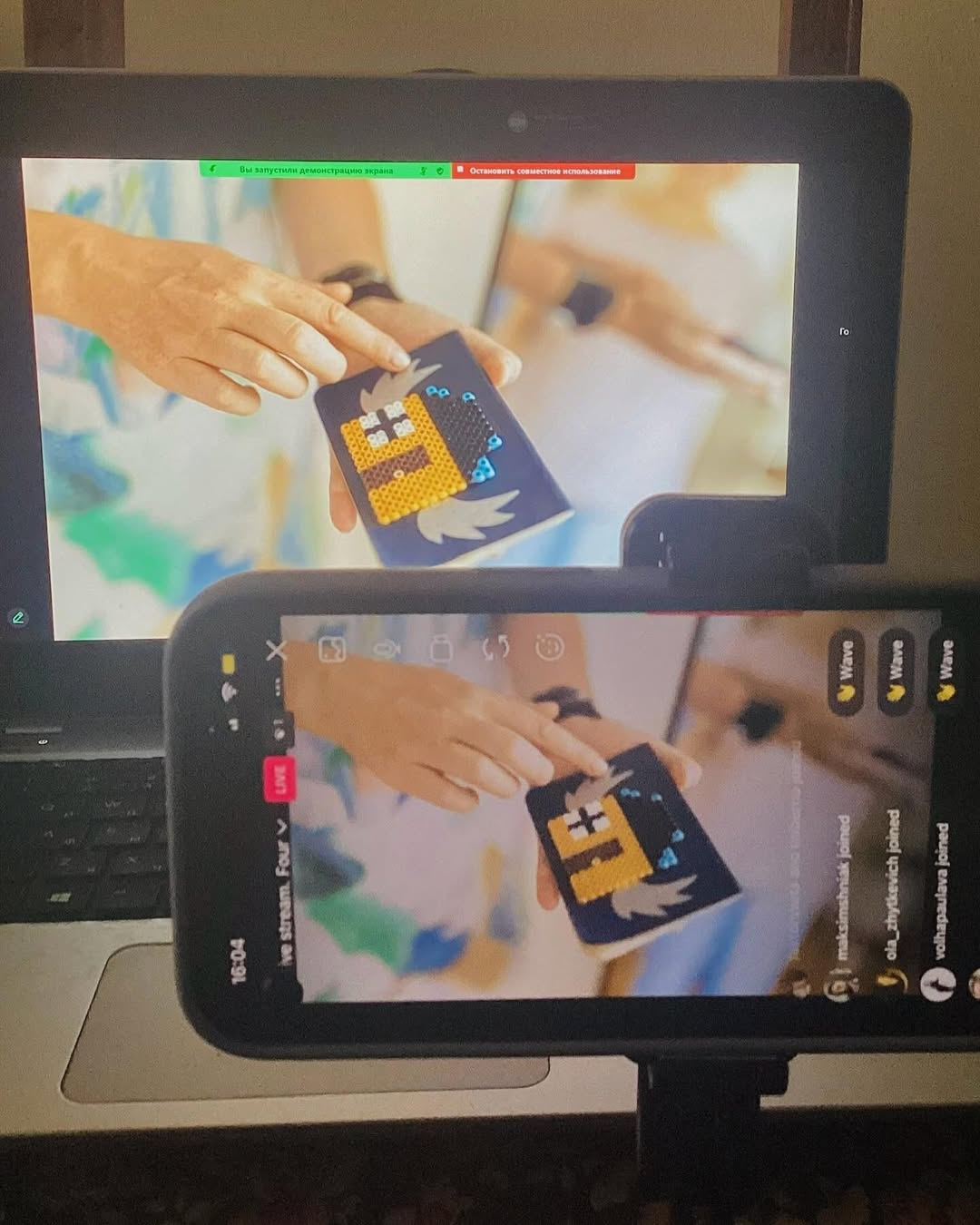

And at that moment, I didn’t have documents allowing me to leave Portugal. I realized this four months before the event. At first, I got nervous, but then I thought: limitations provide another kind of freedom and push toward new ideas. So I created the project virtually.

It was a kind of telebridge. The jewelers recorded their migration stories in audio and video, and for five days straight, via live Zoom broadcasts, I showed these stories to anyone who wanted to join. Sometimes I interrupted the broadcast to talk with virtual visitors. People from Germany, Australia, France, and other countries joined. They shared their own migration stories, and we discussed the jewelers’ experiences. It was a very heartfelt, intimate space – however strange that may sound about something virtual.

— Did you feel the project worked?

— Yes, I really liked that format and was satisfied with everything. As my friend said: “It’s the ideal format for introverts who feel uncomfortable at crowded exhibitions.”

Photo of Elena Karpilova from her exhibition during the Munich Jewelry Week / 2025.

Two Venices in a row

— Besides jewelry, you are also engaged in informal education for children. Tell us about your School of Architectural Thinking.

— The School is a research project consisting of more than 16 studios on different topics: from architecture and contemporary art to political science and economics. All classes are part of one unified program, taught by practicing specialists.

The School of Architectural Thinking started in Minsk back in 2016. At that time, Alexander Novikov (the School’s co-founder) and I were discussing our future and the future of the country and realized that both of us wanted to influence the new generation, to do something important and educational. We both had teaching experience, and in 2016 we held our first summer session for children at the Botanical Garden. Alexander contributed architectural expertise, while I brought experience as an artist, art historian, educator, and methodologist. That’s how it all began.

— How did the School reach the international level?

— From the start, we didn’t intend to stay within Minsk. We began searching worldwide for conferences on children’s architectural education that we could apply to. At that time, nearly 10 years ago, the field was just emerging, and we were among the first to present at different forums. As a result, major media began writing about us, we were invited to collaborate with organizations, and we were even nominated for awards. In 2022, the School was recognized in London as the best international organization by the Thornton Education Trust – the only institution specializing in research and promotion of initiatives in architectural education for children and youth.

— Among your achievements is participation in two Venice Biennales in a row – both art and architecture, the most high-profile events in the art world. How did that happen?

— That’s a long and important story for us. We always wanted to take part in the Biennale, so back in 2020 we were already making arrangements with five different national pavilions. We came up with a project, sent them the concept, and everything was agreed. But then the pandemic began, followed by other well-known events – and the Biennale was no longer a priority.

Then we learned the theme of the next Art Biennale – Foreigners Everywhere – and realized right away that our project was exactly about that. We are all foreigners, both literally and metaphorically. The Biennale took place in 2024, and by then the School was already in exile, working with migrant children. Our project was called Children Everywhere, with the idea that children are “temporary foreigners” in the adult world. Our students invented street games, in which Biennale participants and visitors were supposed to join. As a result, we took part in the Art Biennale unofficially, alongside all the events on Garibaldi Street – the main hub for artists during the Biennale.

Photos of the School of Architectural Thinking from the Venice Biennale / 2025.

— But you also got into the official program.

— Yes, that happened this year. After our experience at the Art Biennale, we decided to submit our project to the Architecture Biennale. This year’s curator, Carlo Ratti, known for projects at the intersection of architecture and technology, decided to take the entire exhibition into the city, turning Venice itself into a laboratory, and announced an open call for projects in the main program. We applied – and got in!

We participated officially and gave a lecture as part of the conference program. We realized our project, also related to games and interaction with the city, at Piazza San Marco, in the Giardini, and in the Nordic Pavilion.

It’s telling that we applied for four grants from Belarusian initiatives to support our participation, at least to help children from Belarus who joined us, and ourselves as well. But we received no support. We were refused with explanations like: “This project is unimportant and will not have a long-term impact on Belarusian culture.” My reaction? I laughed out loud. For the first time in history, the world’s most prestigious architectural event included a project with Belarusian roots, organized by Belarusians, about freedom and inclusion! I’ll leave the competence of those grant judges without comment. We will manage on our own – the main thing is that the world understands and supports us.

— What are the School’s plans now?

— We want to move forward. Our goal is not to make the project huge, because that often leads to superficiality. We are interested in working with a small group of children, giving deep knowledge, and at the same time implementing significant international projects. We will also participate in the next Venice Biennale. Its theme will be In Minor Keys.

We work in Lisbon and online. Online, we would like to work with many more children, because it is a good format not only for new knowledge but also for maintaining community, finding friends, and staying connected. In November, I’ll give a workshop in Boston about Belarusian traditional architecture and possible speculations on that theme. The School is a process and a living organism. It changes, and I change with it. We influence each other.

Elena Karpilova is author of articles and content for Art Jewelry Forum.

Founder and Head of the interdisciplinary project Architectural Thinking School for Children (since 2016).

Finalist of the AGC Italy - Association of Contemporary Jewellery's Maria Cristina Bergesio Award 2024. Member AGC (Association of Contemporary Jewellery)

Jewellery creator and analytic in Instagram page Karpilova.

Since May 2022 lives in Lisbon, Potugal.

Перадрук матэрыялу або фрагментаў матэрыялу магчымы толькі з пісьмовага дазволу рэдакцыі.

Калі вы заўважылі памылку ці жадаеце прапанаваць дадатак да апублікаваных матэрыялаў, просім паведаміць нам.

Elena Karpilova is author of articles and content for Art Jewelry Forum. Founder and Head of the interdisciplinary project Architectural Thinking School for Children (since 2016). Finalist of the AGC Italy - Association of Contemporary Jewellery's Maria Cristina Bergesio Award 2024. Member AGC (Association of Contemporary Jewellery) Jewellery creator and analytic in Instagram page Karpilova.

Since May 2022 lives in Lisbon, Potugal.

Перадрук матэрыялу або фрагментаў матэрыялу магчымы толькі з пісьмовага дазволу рэдакцыі.

Калі вы заўважылі памылку ці жадаеце прапанаваць дадатак да апублікаваных матэрыялаў, просім паведаміць нам.

SHARE:

Чытаць таксама:

FOLLOW US

INSTAGRAM TELEGRAM TIKTOK FACEBOOK YOUTUBE

© Chrysalis Mag, 2018-2025

Reprinting of materials or fragments of materials

is allowed only with the written permission